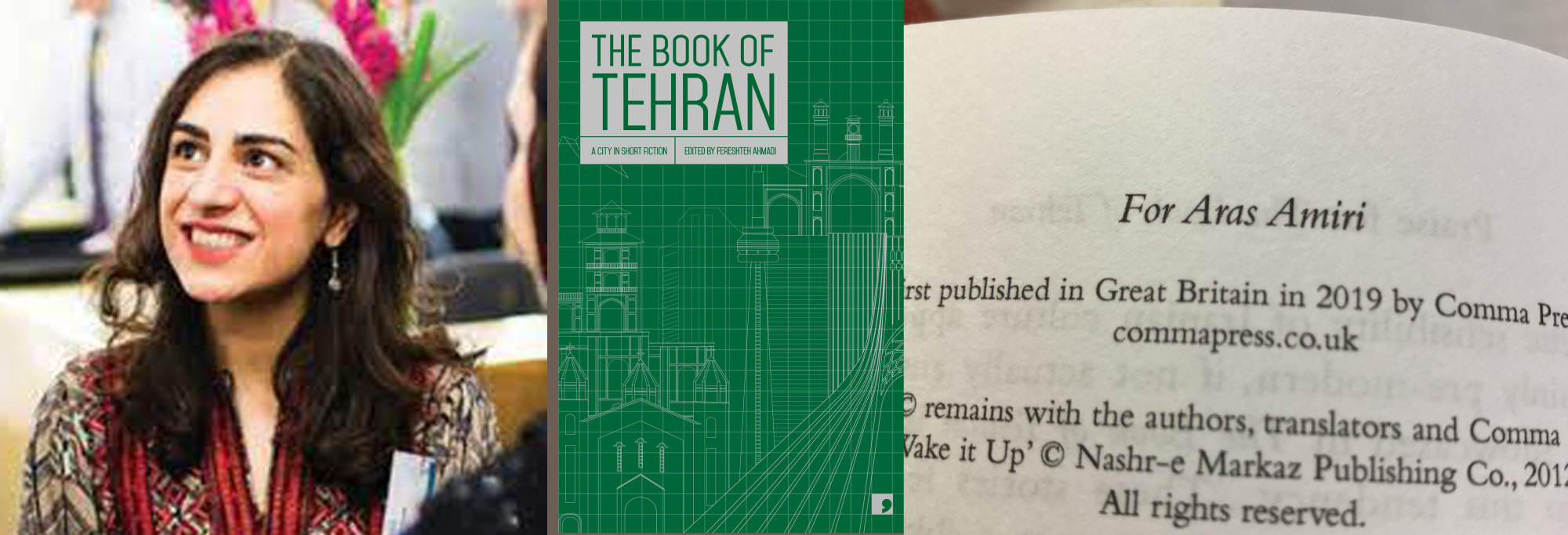

On the Release of Aras Amiri

First published, 21 January 2022.

Comma Press was overjoyed to hear last week's news that British Council worker Aras Amiri has finally been freed by the Iranian government and allowed to return to the UK. For the record, this is the kind of work she was doing.

In late 2017 Comma Press was lucky enough to be approached by Visiting Arts to collaborate on a project it had been working on with other partners for a number of years involving Iranian fiction writers and translators. Using a network of Persian-language writers, readers and translators, VA planned to develop a set of resources for publishers and translators interested in Persian literature in the future. Visiting Arts also wanted to publish an anthology of short stories reflective of the rich and diverse state of contemporary Iranian literature, having gathered a shortlist of around 30 new, previously untranslated short stories and commissioned English language synopses of them. Comma felt extremely privileged to be involved in this work, and was keen to construct a 'Book of Tehran' out of the shortlist, to fit into its ongoing Reading the City translation series that had already featured cities as diverse as Havana, Khartoum and Gaza.

As this was such a collective effort, various contributors were involved in the selection process, including the novelist Fereshteh Ahmadi, who was on a VA-sponsored writers residency in the UK at the time, and an Iranian curator and arts consultant at the British Council, called Aras Amiri. Through a number of conference Skype calls, the various partners worked through the synopses and whittled the shortlist down to the ten stories that would make up the final collection. With the translation set in motion, Aras emailed Comma in March 2018 to say she was going away for a week but would catch up on her return.

Nothing was then heard from Aras for a long while. Eventually, an employee of the British Council who happened to also be a former employee of Comma's, contacted us discretely to explain what had occurred and to ask that we didn’t talk to anyone about it. Aras, on visiting an ailing grandparent in Iran had been arrested on her attempted departure and detained in Evin Prison (the same facility where Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was detained). Aras had been charged with ‘establishing and/or leading an illegal group against the Iranian regime’ (not with spying, as misrepresented in the Western media). Aras’s sentence was only confirmed over a year after her imprisonment in March 2018 (meaning she, and many other political prisoners in Iran including the environmentalist prisoners and Zaghari-Ratcliffe, were held illegally - by Iranian law - without having a confirmed sentence issued). She was sentenced 10 years imprisonment, with simultaneously 12 years travel ban, ban on working in any Iranian governmental or public sector role. (Aras’s appeal against the charges issued in May 2019 were rejected in an appeal court without her or her lawyer present in August 2019. In the earlier court sessions, her lawyer had not been permitted to speak.) When Aras was arrested she was in her early-thirties and halfway through studying for an MA in the philosophy of art at Kingston University, London, focusing on the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno. Unlike Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Aras was not a dual national (the Iranian government doesn't really recognise dual-nationality and regards all British-Iranians as simply Iranian), but was rather an Iranian citizen with British residency. By working with the British Council, Aras was accused of promoting the UK’s soft power agenda, whereas in reality what Aras was doing was exactly the opposite of this, supporting the exporting of Iranian culture into the UK. As well as helping Comma, she had worked with the Edinburgh Festival, Womad, and other festivals, bringing musicians, theatre and film producers, visual artists and writers from Iran or the Persian diaspora to UK audiences.

However, the Iranian judiciary's language in regards to Aras's work seemed only concerned with maintaining a narrative of belligerence between the two nations, saying she was head of the 'Iran desk' of the British Council; in reality she was a junior curator, and the British Council has no 'Iran desk' - this is terminology that belongs to the intelligence services and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, not an arts and culture organisation. As it later transpired, according to Aras, during her 69 days of interrogation, she was offered a deal by the Iranian authorities: Go back and spy for us, or be charged with being a spy for them. (She was offered this deal in later interrogations when she was out on bail, as were other political hostages in her position). This suggests one of two things: either the Iranians genuinely believed the British Council was something it is not - something worth spying on, in intelligence terms; or that they were simply using this pretend 'belief' as a cover story to yet again take a 'liminal citizen' - someone with affinities split between two countries - as hostage, making them a pawn in a much bigger game.1

Almost without exception, all coverage of Aras and Zaghari-Ratcliffe's cases has been couched in the context of on-going /degenerating nuclear treaty negotiations, between Iran on one side and the US and Britain on the other. But the actual reason these citizens were taken hostage was, according to several journalists Comma has spoken to, something a little more embarrassing to the UK. In 1976 the British government struck a deal with Iran, then ruled by the shah, Reza Pahlavi. to deliver 1,500 Chieftain battle tanks and 250 repair vehicles to the Iranian regime. The shah paid £600m for this delivery. After the Iranian Revolution of early 1979, however, a large part of this order hadn't yet been delivered and the British government refused to complete it. This unpaid debt, believed to be in the region of £400 in today's terms, is, for many commentators, the sole reason for Aras and Nazanin's arrest.

Comma was told by its contact at the British Council to take all references to Aras off the eventual Book of Tehran, and it was with heavy hearts (though we couldn't talk about it publicly) that we launched the book in March 2019 at the Edinburgh Iranian Festival. We were not able to mention Aras' name in the book, but Sophia Victoria and Yvette Vaughan Jones at VA agreed it should be dedicated to her cryptically: 'to a friend in Iran'.

After more than three years in jail, months of scattered, indirect, heart-breaking communications, Comma finally heard, in confidence, that on 15 August 2021 the Supreme Court had announced its acquittal of Aras, following an appeal lodged by her lawyer a year previously. She had been released from prison while this review took place back in June 2021, though her travel ban remained in place. Then last week, just minutes before the news broke, we were told Aras was finally safe and sound in the UK, her travel ban had been lifted. Now that the British Council has put out its own statement, we felt it was time to share our story. This is what Aras did. She helped navigate us through the complex cultural and textual complexity of 30 beautifully written short stories - much as she would have helped other cultural organisations appreciate the nuances and value of other nuanced pieces of art or performance.

Thank you Aras for your work on The Book of Tehran, and on the countless other art projects you helped bring about, largely uncredited. We hope you can start to rebuild your work as a champion of all forms of artistic expression from Iran.

Since the original publication of this article in January 2022, we have been able to reprint an edition of The Book of Tehran, with the dedication explicit, and as it should have been (see picture above).

Note

1. Others close to Aras have suggested that not agreeing to collaborate was probably a fairly small factor that led to Aras’s final charge and sentence. Rather the force of the sentence she received was in relation to her commitment and love for Iran and its arts, which, we can assume, reveals the government’s fear of the power of art, culture and the connections this enables, in this respect.