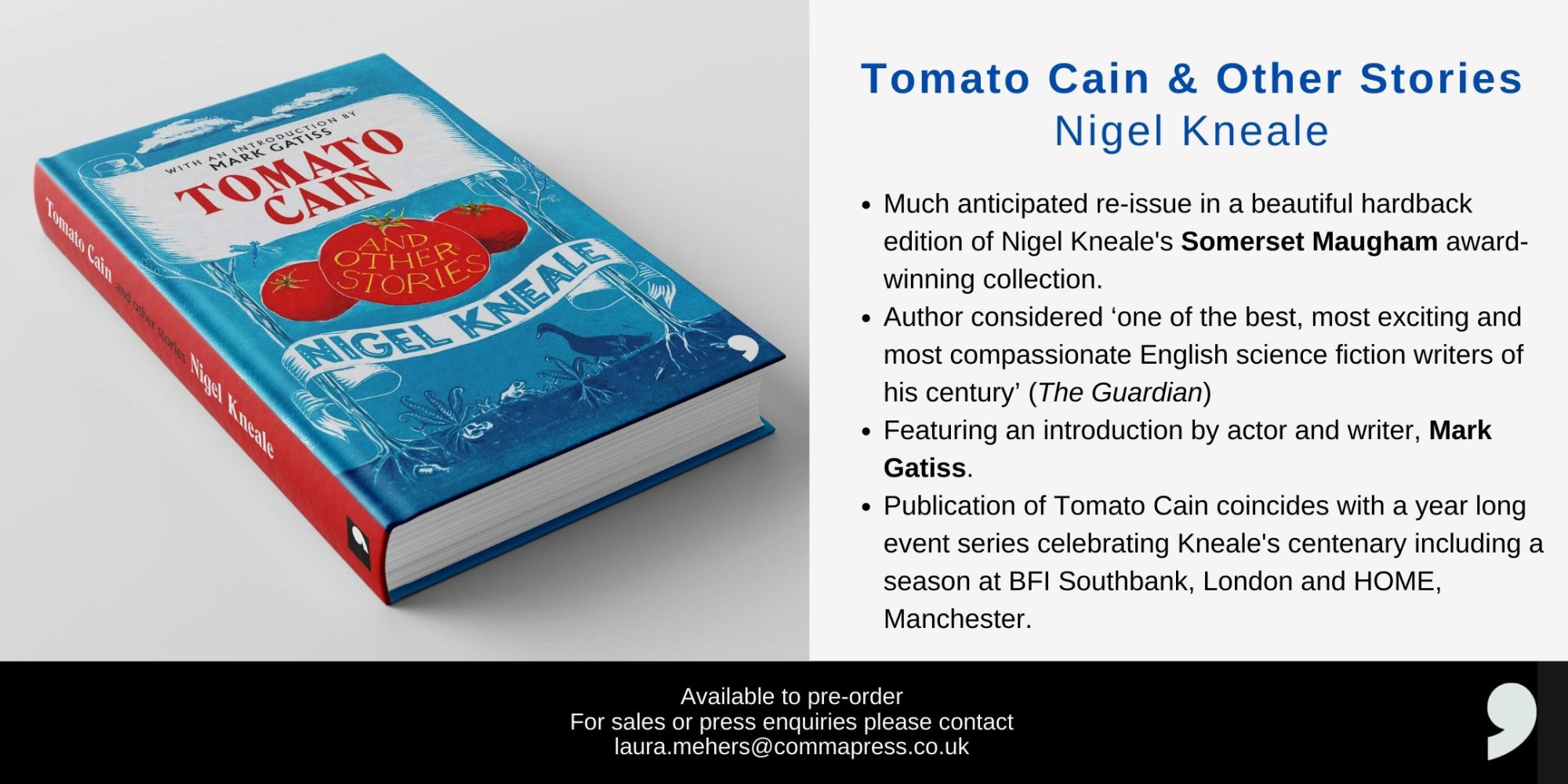

Sneak peek: Tomato Cain and Other Stories

Originally published in 1949, Tomato Cain and Other Stories is the sole collection of short fiction by Nigel Kneale.

Long since out of print, the Comma Press re-issue of Tomato Cain and Other Stories will be published on August 18th 2022 and is available now for pre-orders, featuring two previously lost stories and an introduction by Mark Gatiss.

To celebrate the nearing of the release date, we are sharing the following story from the collection to give a sneak peek into the eerie and delightful collection from British TV legend Nigel Kneale.

––––

The Pond

It was deeply scooped from a corner of the field, a green

stagnant hollow with thorn bushes on its banks.

From time to time, something moved cautiously beneath

the prickly branches that were laden with red autumn berries.

It whistled and murmured coaxingly.

‘Come, come, come, come,’ it whispered. An old man,

squatting frog-like on the bank. His words were no louder than

the rustling of the dry leaves above his head. ‘Come now. Sssst

– ssst! Little dear – here’s a bit of meat for thee.’ He tossed a tiny

scrap of something into the pool. The weed rippled sluggishly.

The old man sighed and shifted his position. He was

crouching on his haunches because the bank was damp.

He froze.

The green slime had parted on the far side of the pool.

The disturbance travelled to the bank opposite, and a large

frog drew itself half out of the water. It stayed quite still,

watching; then with a swift crawl it was clear of the water. Its

yellow throat throbbed.

‘Oh! – little dear,’ breathed the old man. He did not move.

He waited, letting the frog grow accustomed to the air

and slippery earth. When he judged the moment to be right,

he made a low grating noise in his throat.

He saw the frog listen.

The sound was subtly like the call of its own kind. The old

man paused, then made it again.

This time the frog answered. It sprang into the pool,

sending the green weed slopping, and swam strongly. Only its

eyes showed above the water. It crawled out a few feet distant

from the old man and looked up the bank, as if eager to find

the frog it had heard.

The old man waited patiently. The frog hopped twice, up

the bank.

His hand was moving, so slowly that it did not seem to

move, towards the handle of the light net at his side. He

gripped it, watching the still frog.

Suddenly he struck.

A sweep of the net, and its wire frame whacked the

ground about the frog. It leaped frantically, but was helpless in

the green mesh.

‘Dear! Oh, my dear!’ said the old man delightedly.

He stood with much difficulty and pain, his foot on the

thin rod. His joints had stiffened and it was some minutes

before he could go to the net. The frog was still struggling

desperately. He closed the net round its body and picked both

up together.

‘Ah, big beauty!’ he said. ‘Pretty. Handsome fellow, you!’

He took a darning needle from his coat lapel and carefully

killed the creature through the mouth, so that its skin would

not be damaged; then put it in his pocket.

It was the last frog in the pond.

He lashed the water with the handle, and the weed

swirled and bobbed: there was no sign of life now but the little

flies that flitted on the surface.

He went across the empty field with the net across his

shoulder, shivering a little, feeling that the warmth had gone

out of his body during the long wait. He climbed a stile,

throwing the net over in front of him, to leave his hands free.

In the next field, by the road, was his cottage.

Hobbling through the grass with the sun striking a long

shadow from him, he felt the weight of the dead frog in his

pocket, and was glad.

‘Big beauty!’ he murmured again.

The cottage was small and dry, and ugly and very old. Its

windows gave little light, and they had coloured panels, darkblue

and green, that gave the rooms the appearance of being

under the sea.

The old man lit a lamp, for the sun had set; and the light

became more cheerful. He put the frog on a plate, and poked

the fire, and when he was warm again, took off his coat.

He settled down close beside the lamp and took a sharp

knife from the drawer of the table. With great care and

patience, he began to skin the frog.

From time to time, he took off his spectacles and rubbed

his eyes. The work was tiring; also the heat from the lamp

made them sore. He would speak aloud to the dead creature,

coaxing and cajoling it when he found his task difficult. But

in time he had the skin neatly removed, a little heap of

tumbled, slippery film. He dropped the stiff, stripped body

into a pan of boiling water on the fire, and sat again, humming

and fingering the limp skin.

‘Pretty,’ he said. ‘You’ll be so handsome.’

There was a stump of black soap in the drawer and he

took it out to rub the skin, with the slow, over-careful motion

that showed the age in his hand. The little mottled thing began

to stiffen under the curing action. He left it at last, and brewed

himself a pot of tea, lifting the lid of the simmering pan

occasionally to make sure that the tiny skull and bones were

being boiled clean without damage.

Sipping his tea, he crossed the narrow living room. Well

away from the fire stood a high table, its top covered by a

square of dark cloth supported on a frame. There was a faint

smell of decay.

‘How are you, little dears?’ said the old man.

He lifted the covering with shaky scrupulousness. Beneath

the wire support were dozens of stuffed frogs.

All had been posed in human attitudes; dressed in tiny

coats and breeches to the fashion of an earlier time. There

were ladies and gentlemen and bowing flunkeys. One, with

lace at his yellow, waxen throat, held a wooden wine cup. To

the dried forepaw of its neighbour was stitched a tiny glassless

monocle, raised to a black button eye. A third had a midget

pipe pressed into its jaws, with a wisp of wool for smoke. The

same coarse wool, cleaned and shaped, served the ladies for

their miniature wigs; they wore long skirts and carried fans.

The old man looked proudly over the stiff little figures.

‘You, my lord – what are you doing, with your mouth so

glum?’ His fingers prised open the jaws of a round-bellied frog

dressed in satins; shrinkage must have closed them. ‘Now you

can sing again, and drink up!’

His eyes searched the banqueting, motionless party.

‘Where now – ? Ah!’

In the middle of the table, three of the creatures were fixed

in the attitudes of a dance.

The old man spoke to them. ‘Soon we’ll have a partner for

the lady there. He’ll be the handsomest of the whole company,

my dear, so don’t forget to smile at him and look your

prettiest!’

He hurried back to the fireplace and lifted the pan;

poured off the steaming water into a bucket.

‘Fine, shapely brain-box you have.’ He picked with his

knife, cleaning the tiny skull. ‘Easy does it.’ He put it down on

the table, admiringly; it was like a transparent flake of ivory.

One by one, he found the delicate bones in the pan, knowing

each for what it was.

‘Now, little duke, we have all of them that we need,’ he said

at last. ‘We can make you into a picture indeed. The beau of the

ball. And such an object of jealousy for the lovely ladies!’

With wire and thread he fashioned a stiff little skeleton,

binding in the bones to preserve the proportions. At the top

went the skull.

The frog’s skin had lost its earlier flaccidness. He threaded

a needle, eyeing it close to the lamp. From the table drawer

he now brought a loose wad of wool. Like a doctor

reassuring his patient by describing his methods, he began to

talk.

‘This wool is coarse, I know, little friend. A poor

substitute to fill that skin of yours, you may say: wool from

the hedges, snatched by the thorns from a sheep’s back.’ He

was pulling the wad into tufts of the size he required. ‘But

you’ll find it gives you such a springiness that you’ll thank

me for it. Now, carefully does it –’

With perfect concentration he worked his needle

through the skin, drawing it together round the wool with

almost untraceable stitches.

‘A piece of lace in your left hand, or shall it be a

quizzing-glass?’ With tiny scissors he trimmed away a

fragment of skin. ‘But wait – it’s a dance and it is your right

hand that we must see, guiding the lady.’

He worked the skin precisely into place round the skull.

He would attend to the empty eye-holes later.

Suddenly he lowered his needle.

He listened.

Puzzled, he put down the half-stuffed skin and went to

the door and opened it.

The sky was dark now. He heard the sound more dearly.

He knew it was coming from the pond. A far-off, harsh

croaking, as of a great many frogs.

He frowned.

In the wall cupboard he found a lantern ready trimmed,

and lit it with a flickering splinter. He put on an overcoat

and hat, remembering his earlier chill. Lastly he took his net.

He went very cautiously. His eyes saw nothing at first,

after working so close to the lamp. Then, as the croaking came

to him more clearly and he grew accustomed to the darkness,

he hurried.

He climbed the stile as before, throwing the net ahead.

This time, however, he had to search for it in the darkness,

tantalised by the sounds from the pond. When it was in his

hand again, he began to move stealthily.

About twenty yards from the pool, he stopped and

listened.

There was no wind and the noise astonished him.

Hundreds of frogs must have travelled through the fields to

this spot; from other water where danger had arisen, perhaps,

or drought. He had heard of such instances.

Almost on tiptoe he crept towards the pond. He could see

nothing yet. There was no moon, and the thorn bushes hid the

surface of the water.

He was a few paces from the pond when, without

warning, every sound ceased.

He froze again. There was absolute silence. Not even a

watery plop or splashing told that one frog out of all those

hundreds had dived for shelter into the weed. It was strange.

He stepped forward, and heard his boots brushing the

grass.

He brought the net up across his chest, ready to strike if

he saw anything move. He came to the thorn bushes, and still

heard no sound. Yet, to judge by the noise they had made, they

should be hopping in dozens from beneath his feet.

Peering, he made the throaty noise which had called the

frog that afternoon. The hush continued.

He looked down at where the water must be. The surface

of the pond, shadowed by the bushes, was too dark to be seen.

He shivered, and waited.

Gradually, as he stood, he became aware of a smell.

It was wholly unpleasant. Seemingly it came from the

weed, yet mixed with the vegetable odour was one of another

kind of decay. A soft, oozy bubbling accompanied it. Gases

must be rising from the mud at the bottom. It would not do

to stay in this place and risk his health.

He stooped, still puzzled by the disappearance of the

frogs, and stared once more at the dark surface. Pulling his net

to a ready position, he tried the throaty call for the last time.

Instantly he threw himself backwards with a cry.

A vast, belching bubble of foul air shot from the pool.

Another gushed up past his head; then another. Great

patches of slimy weed were flung high among the thorn

branches.

The whole pond seemed to boil.

He turned blindly to escape, and stepped into the thorns.

He was in agony. A dreadful slobbering deafened his ears: the

stench overcame his senses. He felt the net whipped from his

hand. The icy weeds were wet on his face. Reeds lashed him.

Then he was in the midst of an immense, pulsating

softness that yielded and received and held him. He knew he

was shrieking. He knew there was no one to hear him.

An hour after the sun had risen, the rain slackened to a light

drizzle.

A policeman cycled slowly on the road that ran by the

cottage, shaking out his cape with one hand, and halfexpecting

the old man to appear and call out a comment on

the weather. Then he caught sight of the lamp, still burning

feebly in the kitchen, and dismounted. He found the door

ajar, and wondered if something was wrong.

He called to the old man. He saw the uncommon

handiwork lying on the table as if it had been suddenly

dropped; and the unused bed.

For half an hour the policeman searched in the

neighbourhood of the cottage, calling out the old man’s name

at intervals, before remembering the pond. He turned

towards the stile.

Climbing over it, he frowned and began to hurry. He was

disturbed by what he saw.

On the bank of the pond crouched a naked figure.

The policeman went closer. He saw it was the old man,

on his haunches; his arms were straight; the hands resting

between his feet. He did not move as the policeman

approached.

‘Hallo, there!’ said the policeman. He ducked to avoid the

thorn bushes catching his helmet. ‘This won’t do, you know.

You can get into trouble –’

He saw green slime in the old man’s beard, and the staring

eyes. His spine chilled. With an unprofessional distaste, he

quickly put out a hand and took the old man by the upper

arm. It was cold. He shivered, and moved the arm gently.

Then he groaned and ran from the pond.

For the arm had come away at the shoulder: reeds and

green water-plants and slime tumbled from the broken joint.

As the old man fell backwards, tiny green stitches glistened

across his belly.

Nigel Kneale’s Tomato Cain and Other Stories is available to pre-order via the Comma Press website here. If you are a bookshop or library interested in stocking this title please get in touch with us directly at laura.mehers@commapress.co.uk